In Ireland to date, little objective information about the pros and cons of wind development has been made available to the public. We seek to address that imbalance.

Blue Ireland 2023

Offshore renewable infrastructure is still infrastructure. It needs to be subject to best-practice planning and design and requires rigorous evaluation using both environmental impacts assessments (EIA) and strategic environmental assessments (SEA). When developing offshore renewable projects, it is therefore crucial to adopt an ecosystem-based approach, apply well-considered marine zonation, and support ocean resilience by staying within ecosystem boundaries.

WORLD WILDLIFE FUND

Emphatically yes. It is absolutely clear that there is an imperative need to decarbonise our energy supply and that the development of renewable energy will be a critical step in this process. Given that we face major challenges due to climate change and biodiversity collapse, the need to re-think is both critical and urgent. We support the development of renewable energy when, in line with best international practice, sites are carefully selected to avoid the negative environmental impacts associated with offshore wind and when proposed projects are subject to a modern democratic marine planning process, for example ecosystem-based Marine Spatial Planning.

Blue Ireland exists to advocate for proper Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) and appropriate siting of offshore renewable energy (ORE) developments in order to optimise benefits (e.g., carbon capture and fish stocks) and minimise damaging impacts on the marine environment (e.g., damage to ecosystems and biodiversity). The issue is that, as a result of lax permitting regimes, at present all ORE projects in Ireland are proposed on sites self-selected by developers, with no regard for environmental impacts on marine life, livelihoods, or the Irish coastline.

The legislation governing construction at sea is The Foreshore Act 1933. This law gives power to a Minister to grant foreshore licences (for site investigation) and leases (for construction) for proposed offshore projects. It has been used by successive Ministers over the past 25 years to give consent to prospective offshore wind developers who selected areas of the foreshore (out to 12 nautical miles or 22.2 km) on a ‘first-come-first-served’, ad hoc, basis, with no environmental constraints. The consequences of this developer-led planning and lax regulation are widespread, posing a significant threat to valuable marine habitats and species and the democratic process.

Firstly, many current development proposals are targeting high biodiversity value sites that are, in fact, completely unsuitable for development. See the Fair Seas report ‘Revitalising our Seas’ for further details.

Secondly, over the past decade, most of the original stakeholders have sold on all or part of their dubious interests, netting them large profits in return for access to State-owned foreshore. In February 2020, for example, it was reported that French Energy giant, EDF, acquired a 50% stake in the proposed Codling windfarm from a company linked to developer, Johnny Ronan, at an estimated cost of €100 million. Just months earlier, in June 2019, official documentation shows that €5m was owed by Codling in unpaid fees to the State, that it was considered that Codling was close to being in development default and that the Department was contemplating termination of the lease. By 19 May 2020, all this changed. It was announced that Codling had been classified as a ‘relevant’ project, and would be fast-tracked through the consenting process. Unbelievably, all this happened in the absence of any environmental assessment or public involvement, at a time when the country was experiencing the early chaos of the Covid pandemic.

Sites on which major developments are now proposed were selected more than 20 years ago on a first-come-first served basis, in the absence of any environmental safeguards. They were not selected based on where sustainable development could take place, but on the technology available at the time. In the intervening years, offshore wind technology has changed immeasurably. Developments no longer need to be sited in shallow water and the advent of floating wind has created the potential to site turbines further out to sea, where winds are stronger and where the worst impacts of developments on sensitive coastal waters can be mitigated.

Because of this historic mis-management, the reality is that, in spite of intensive efforts by government to chart a pathway to completion for these legacy projects, because they are effectively the wrong developments in the wrong places, many are being challenged through Judicial Review. Not alone is this extremely costly for the State (essentially the tax-payer) it means that (1) whether or not these…

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is defined as ‘a process by which the relevant Member State’s authorities analyse and organise human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives’ (EU, 2014). The European Union (EU) Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (2014) required all Member States with marine territories to prepare ecosystem-based maritime spatial plans for their waters by March 2021. This approach allows for maximising the benefits of our seas, while minimising the harm to our coastal habitats in order to ensure that the common good is served.

Ecosystem-based planning seeks to identify and understand the important ecological characteristics of an area, and then to design plans to guide the development of ecologically responsible human activities in that space.

Ecosystem-based planning focuses on the diverse benefits provided by functioning marine ecosystems, rather than on single species, habitat or ecosystem service. An ecosystem-based approach ensures that the protected species, habitats and the unique ecosystems that support them are maintained. All such species/habitats are interconnected and cannot be considered independently. Such benefits or services include vibrant commercial and recreational fisheries, biodiversity conservation, renewable energy from wind or waves and coastal protection. Of the four factors listed here, biodiversity conservation, inshore fisheries and coastal protection are threatened by the development of current Irish government plans for coastal offshore wind development.

Ireland, like other EU countries, was obliged to prepare an ecosystem-based spatial plan by March 2021 but, unfortunately, the plan developed by Ireland does not comply with the EU MSP Directive.

The National Marine Planning Framework (NMPF) adopted by the Irish Government in May 2021 is not ecosystem-based. It provides a policy framework for marine planning but does not specify where activities will take place at sea or set out regionally differentiated priorities for the use and protection of Ireland’s marine space (Walsh, 2022). The NMPF, therefore, fails to meet the core requirements of the EU MSP Directive and cannot be considered as a marine spatial plan.

Regulation of offshore wind development varies throughout the world. This is sometimes justified with claims that the sector is nascent, i.e., emerging, and consequently some countries are only in the process of developing policy.

However, much of Ireland’s environmental law is grounded in long-standing EU laws and Directives which are applicable within individual Member States. This includes the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC), the Birds Directive (2009/147/EC), the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC), the Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive (2001/42/EC), the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive (2011/92/EU), and the EU Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (2014/89/EU). Ireland has continued to process applications for offshore wind without regard to a number of these Directives. This failure to comply with the Directives has resulted, on a number of occasions, in Ireland being found to be in breach of EU law, the most recent judgement against Ireland made on 30 June 2023.

A comprehensive briefing note prepared by Coastal Concern Alliance outlines the diverse consenting processes for ORE in different EU countries.

No. Our well justified fear is that important functioning marine and coastal ecosystems will be destroyed as a result of Ireland’s lax permitting regime for offshore wind. This, combined with the government’s inordinate delay in putting in place protection for marine habitats and species (Marine Protected Areas), and our awareness of how critically important it is to preserve and restore these ecosystems to avoid biodiversity loss and help to mitigate climate change, is why we have initiated the Blue Ireland campaign.

We are fully supportive of the development of offshore renewables when developments are appropriately sited and managed under a modern, democratic, ecosystem-based marine planning regime.

Site-selection is internationally accepted as the most important factor in mitigating the biodiversity impacts of wind and solar developments. To-date, in Ireland, site-selection for offshore wind development has been exclusively developer-led, with no government oversight or Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) to assess cumulative impacts, as is required under the SEA Directive.

People may imagine that the seabed around our coast consists of sand; in fact, it consists of so much more, with rocky terrains and glacial deeps, biogenic reefs (made by living organisms) and geogenic reefs (resulting from geological processes) all hosting a huge diversity of life forms.

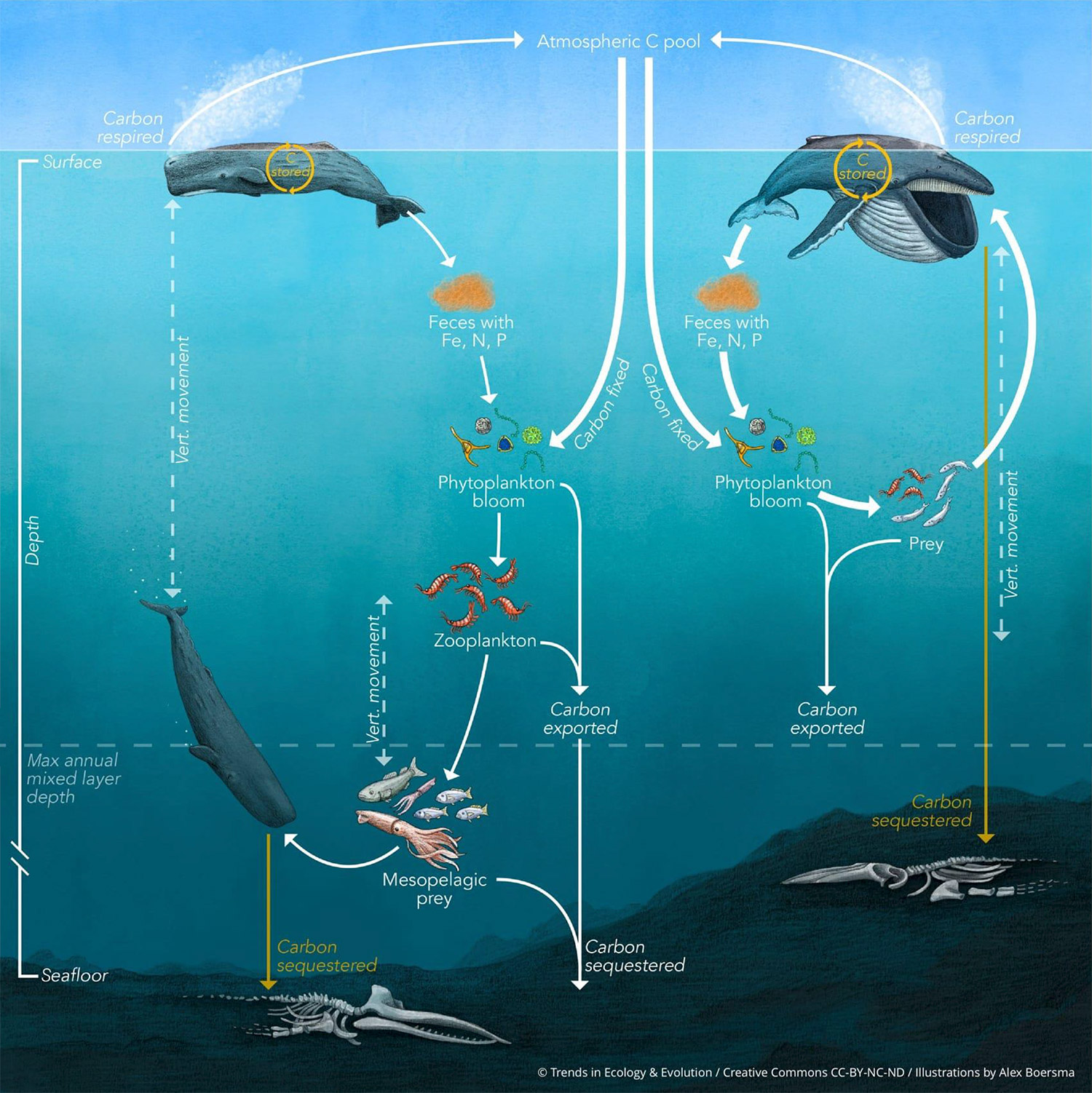

Information shown on NASA maps indicates the dense concentrations of phytoplankton that skirt Ireland’s coast. Phytoplankton, essential to our survival, is arguably the most important life on earth. It produces more than 50% of the earth’s oxygen through photosynthesis and is highly effective at absorbing carbon from the atmosphere. Phytoplankton are the foundation of the aquatic food web, the primary producers, feeding everything from microscopic, animal-like zooplankton to multi-ton whales. Small fish and invertebrates also graze on the plant-like organisms, and, in turn, smaller animals are eaten by bigger ones.

The presence of these microscopic creatures explains the rich biodiversity that we in Ireland enjoy in our coastal waters. In fact, our seas and sea beds contain Ireland’s most pristine functioning ecosystems. Though overfishing has had impacts, vast areas of undamaged seabed remain intact, in stark contrast to our lands, where almost every inch has been impacted by human disturbance.

Mudflats and sandflats, for example, not only host biodiverse habitats, they are also a really effective carbon sink. Seagrass meadows, found dotted around the Irish coast, stabilise the sea floor and can absorb carbon 35 times faster than the Amazon rainforest.

Because of developer-led planning, many proposed wind developments are sited where their construction, and even initial site investigations, have the potential to have significant negative impacts on some of these important marine ecosystems.

Current development proposals traverse or adjoin many important ecologically valuable areas, Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), designated to protect marine habitats such as reefs, seagrass and sandbanks, and Special Protection Areas (SPA), to protect rare seabird species such as terns, puffin and kittiwakes. Siting of developments in close proximity to these protected areas poses an unnecessary risk to Ireland’s biodiversity, threatened species and habitats.

Until a few months ago, just 2.1% of Ireland’s maritime area was even nominally protected in SACs and SPAs although our target was to have 10% fully protected by 2020 and by 2030, 30% of the marine area should be designated and managed to ensure it is truly safeguarded. Some progress is being made but, in the meantime, Blue Ireland believes that it is vital that we value all rich marine habitats and species because the future of the planet, and our future, depends on it.

With regard to the areas which Ireland has designated as SACs and SPAs, the Irish government has consistently failed to fulfil their obligations and adequately protect those areas, resulting, on a number of occasions, in Ireland being found to be in breach of EU law, with the most recent judgement against Ireland being handed down on 30 June 2023.

Poorly sited wind farms can have a detrimental effect on healthy marine ecosystems. The failure of the government to adequately manage site-selection, as well as substantial delays in designation of Marine Protected Areas means that currently proposed offshore wind developments pose a serious threat to Ireland’s marine biodiversity, with knock-on effects for natural carbon capture.

To be completed.

No, there is no reliable evidence to support this claim. An early study on small offshore wind turbine foundations suggests an increase in the variety of species present close to the turbine bases due to the introduction of hard substrata (rocks and concrete) around the turbine bases. This may be due to

the fact that fishing is not allowed within the wind farm areas. It is known from a recently published long-term study carried out in Belgium that impacts change over time. After a ten-year period of monitoring, while initially it looked as if there might be some positive changes, the authors reported ‘slimeification’ and decline of the initial invasive species, effectively leading to significant deterioration of the original ecosystem. The study concludes that earlier reports on offshore wind turbines as potential biodiversity hotspots should be considered premature.

In short, turbines and hard substrata do not belong in functioning, high biodiversity, sandy or soft mud ecosystems. Hard structures such as these facilitate the development and proliferation of different and potentially invasive species that will out-compete native species resulting in reduced biodiversity.

Did you know that sand eels, on which whales and endangered bird species feed, require sand to survive and reproduce? Construction of windfarms on sandbanks would require the removal of 3-6 metres depth of sand, destroying this important sandy habitat. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red-listed Puffin and Kittiwake feed almost exclusively on sand eel, which means construction of wind farms on sandbanks has a direct impact on species protected under the Birds and Habitats Directive.

Everything! Marine ecosystems depend on the food web, which starts with phytoplankton. Development of offshore wind is reported to have an impact on phytoplankton production. If we destroy phytoplankton, everything else dies. Ocean ecosystems provide 50-80% of global oxygen and are among the world’s most effective carbon sinks. So, in short, these ecosystems are vital for regulation of climate, the air we breathe and life on earth. When the ocean breathes out, we breathe in!

Areas containing natural reefs, seagrass, kelp forests and sea-pens, are examples of marine ecosystems that very efficiently capture carbon from the atmosphere. For example, seagrass beds capture carbon 35 times faster than a rainforest. Reefs give life to our seas providing shallow, light-filled waters for phytoplankton to bloom, fish to spawn, sharks and whales to feed. Protecting whales and allowing their numbers to increase is another really effective way to capture atmospheric carbon in the ocean.

Phytoplankton captures carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, just like trees. Unfortunately, if it is not consumed, phytoplankton can degrade and return the carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, rather than store it in the deep oceans. Whales, a vital part of the marine ecosystem, consume large amounts of phytoplankton (e.g. Blue whales feed on 16 tons per day), which they then defecate (poo out) onto the ocean floor, where it forms a stable carbon sink. In addition, the resulting release of inorganic nutrients (e.g. iron, nitrates, phosphates, silicates and calcium) from the faeces stimulates increased phytoplankton production (just like fertilising your garden). At the end of their lives, when whales die, their bodies fall to the ocean floor, resulting in even further carbon capture and storage (See image below).

Excess carbon dioxide in our atmosphere creates global problems. Globally, 10 Gt would have to be removed annually to keep the global temperature increase to below 1.5 degrees, as committed to under the Paris agreement. However, because it is present in minute concentrations (approx. 419.08 parts per million) it very difficult and inefficient to remove using man-made systems. In contrast, marine and terrestrial ecosystems (e.g., oceans, bogs, rainforest) have evolved over millions of years to become exceptionally efficient at capturing and storing carbon. While there is much talk these days about carbon capture technologies, any technology developed by humans is going to be a highly inefficient and expensive alternative to the natural carbon capture provided by healthy functioning ecosystems.

A typical wind development using fixed bottom foundations consists of wind turbine generators, associated foundations, offshore substations and associated foundations, inter-array cables linking each turbine to the substation and export cables which bring the power to an onshore substation. Construction of a typical wind farm requires hundreds of kilometers of electrical cabling and thousands of tons of steel, rock and concrete.

Sites are prepared by clearing the natural seafloor. Turbines (up to 320m height above sea level) are then erected by embedding them deeply into the seabed. Various techniques may be used to drive these huge structures to depths that will ensure their stability, but irrespective of the technique used, none of the original seafloor integrity is likely to survive this operation. Similarly, a range of techniques can be used to embed and anchor the high voltage electrical cables into the seabed. Routes can be prepared by dredging, ploughing or trenching to some depth, then cables laid, sometimes on concrete ‘matressing’, and covered with concrete or rock that can be up to 5 metres wide. If cables are laid on sandbanks, prior to the cables being laid, 3-6 meters of the surface sand must be removed to create an appropriate base for the construction. This is the living layer of the ecosystem in which the sand eels live, so cable laying on sandy surfaces, effectively totally removes the functioning part of that important ecosystem.

A wind turbine consists of a tall cylindrical tower with a nacelle (generator housing) on top which contains the functional components of the turbine. Attached to the nacelle are three blades which rotate, driven by the force of the wind. Turbine nacelles also rotate through 360 degrees in order to keep the blades facing into the wind. The specifications of turbines vary between manufacturers. Overall height from the sea level to the blade tip can reach over 300 meters (1000 feet). The turbine tower diameter is approximately 7-9 meters. Blade tips can reach speeds of 195 km/h when rotating.

In Ireland, the government has imposed no restriction on proximity of wind farms to shore. For this reason, developers have targeted sites that are significantly closer to shore than would be permitted in other EU countries.

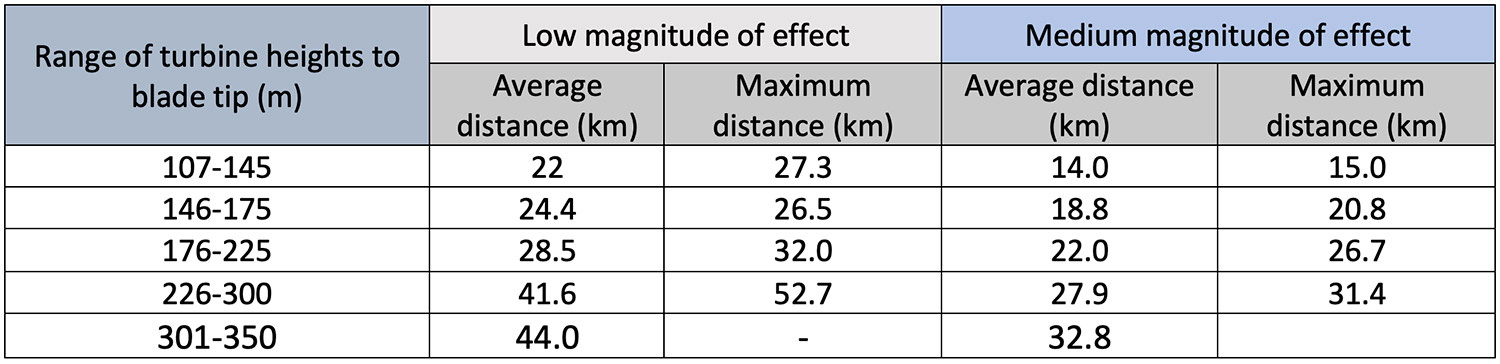

Turbine distance to shore has changed with advances in technology. The seven turbines that were constructed 20 years ago in Phase One of the Arklow Bank development are 124 meters high, while turbine height for proposed developments are over 300 meters. (To put this into context, the blade of proposed turbines would be similar in length to the Dublin Spire, 121 meters high).

In the early stages of offshore wind development, it was a huge accomplishment to sink a turbine foundation into 10 meters of water. This explains why some early developments are located in shallow water relatively close to shore. Advancements in technology now allow turbine foundations to be installed in up to 70 meters of water and developers are already installing foundations at this depth. This, together with the introduction of floating turbine platforms, means that the majority of current EU and global offshore wind developments are located a minimum of 25 km from the shore.

In simple terms fixed bottom wind turbines are turbines that are individually anchored to the sea bed: some are anchored using a structure called a monopile, others are fixed with what’s called a jacket foundation.

Monopiles are hollow steel cylindrical tubes approximately 8 meters in diameter with wall thicknesses of 8-10cm (imagine a really massive steel drinking straw). Using a hydraulic device, monopiles are hammered into the seabed to depths of between 30-40 meters (or more, for bigger turbines). A turbine is then attached to the monopile via a transition piece. Each monopile requires thousands of tons of rock armour to protect the base of the turbine from hydrodynamic erosion.

Jacket foundations are lattice structures consisting of three or four legs and are normally attached to the seabed by fixing each leg to a pre-driven monopile. Again, thousands of tons of rock are required to protect the base of each leg from hydrodynamic erosion. Current technology allows fixed bottom turbines (using either single monopiles or jacket foundations) to be installed in water up to 70 meters deep.

A floating wind turbine platform is anchored to the seabed and can carry a turbine in water depths of between 80-200 meters. While fixed bottom wind turbines are limited to being sited in waters of approximately 70 meters deep, floating wind turbine platforms allow developers to use deep water locations where wind speeds are stronger, visual impact is less and environmental impacts on the seabed are likely to be minimised, due to less invasive installation and operation phases. The Irish Government has stated that it will not provide any route to market for floating wind before 2030, although applications to develop floating projects are currently being made. No clear explanation has been given for this decision.

Ireland’s only existing offshore wind turbines are situated on the Arklow Bank, approximately 12 km from the shore. The height from the surface of the sea to the tip of the turbine blade is 124 meters (407 feet). Turbine heights currently being proposed can extend 320 meters (1050 feet) from sea level to blade tip.

It is difficult to imagine the scale of such a turbine, but if you have ever seen the Eiffel Tower in Paris, or can picture it in the Parisian skyline, you’re there: modern wind turbines are just four meters shorter than Gustav Eiffel’s tower! Closer to home, consider that the Dublin Spire is 121 meters tall: the same height as one blade on a modern turbine. Try imagining two Dublin Spires stacked lengthways to get an idea of the rotor diameter and then imagine these hoisted another 40-50 meters in the air to allow for clearance above the sea surface—that’s how big modern wind turbines are. Turbines of this size have not yet been installed en masse anywhere in the world, so it is understandable that people find it difficult to conceptualise the size and scale.

Image

Yes. Offshore wind developments currently proposed in Ireland consist on average of around 50 turbines per development. With turbines of approximately 300 meters tall, located 10-15 km from shore these proposed developments would dominate the coastal landscape/seascape. International research suggests that, before they become visually insignificant, wind turbines of this magnitude would need to be located approximately 45 km from shore. In Ireland it is currently being proposed that such enormous turbines could be sited 5-6 km from shore.

The Irish coastline, which is so much part of our collective heritage and identity, remains relatively unspoilt and is of enormous value to the Irish people and visitors to the island. Ireland has an opportunity to adopt a measured, sustainable, innovative and environmentally sensitive approach to offshore renewable energy development, learning from those countries which have already adopted a variety of approaches, policies and technologies. We must argue robustly to protect Ireland’s marine environment, magnificent coastal landscapes and those whose welfare and economic prosperity depends on preserving the ecological and visual integrity and unique quality of this environment.

The Irish government continues to support a developer-led business model for offshore wind. This has allowed developers to identify and lay claim to any site they choose and apply for rights on that site. Currently, four projects have received a route to market (meaning that these projects have been accepted for the government Offshore Renewable Energy Support Scheme (ORESS); North Irish Sea Array (Skerries), Dublin Array (Kish & Bray Banks, South Dublin/Wicklow), Codling Wind Park (Bray/Greystones/Wicklow) and Sceirde Rocks (Connemara).

These sites were targeted by speculative interests more than 20 years ago without any environmental assessment as to their suitability for development. Careful site selection is the most important step in avoiding damaging environmental impacts of wind and solar developments. These historic sites have not been the subject of any Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA), nor are they required to align with a marine spatial plan. The only environment assessments undertaken have been commissioned and paid for by the developers and environmental consultants employed by, or associated with, developers. This is, surprisingly, not illegal, but it underlines the importance of having a robust system to scrutinise submissions made in support of the developers’ proposals. In Ireland no such reliable system of scrutiny exists.

Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a process for the formal, systematic evaluation of the likely significant environmental effects of implementing a plan or programme, before a decision is made to adopt the plan or programme. The SEA Directive requires that all plans and programmes that have the potential to have impacts on the environment are subject to SEA. However, in Ireland, certain plans and programmes have either not been subjected to SEA (Harnessing our Ocean Wealth – An Integrated Marine Plan for Ireland, 2012) or the Directive has been incompletely applied (Offshore Renewable Energy Development Plan, 2014).

The quick answer is no. The illusion that electricity produced from renewable energy sources is cheap has yet to be proven. Two of the early adopters of renewable energy, Denmark and the UK, both have some of the highest consumer electricity prices in Europe at €0.60 kW/h compared to Ireland which currently averages at about €0.42 kW/h and way above the EU average of €0.28 kW/h. Considering that Denmark generates over 70% and the UK 41% of their electricity from renewable sources (mostly wind) it appears that renewable energy will not deliver the lower prices we had hoped for.

On the other hand, electricity should not necessarily be cheap and, though there are social issues to overcome, increasing consumer (and commercial) electricity prices is one of the most effective ways of reducing electricity consumption and as a result, climate impacts.

To cover the initially higher costs involved in generating from renewable sources in Ireland, projects are subsidised. Developers partake in a government Offshore Renewable Energy Support Scheme (ORESS), which guarantees them a fixed price for electricity for the duration of the project. Developers must place bids regarding their supply prices and generation capacity in an auction (ORESS 1) and, in theory at least, the cheapest bids are accepted. A strike (guaranteed) price is determined by Eirgrid and successful developers are then assured of a route to market and a guaranteed price for the electricity their development generates. The auction price is based on contracts for difference, which means if the wholesale (spot) price drops below the strike price, the government will top up the developers to the predetermined strike price. If the wholesale price goes above the strike price, the developers pay back the balance.

This gives developers and investors a safety net, ensuring there is no way projects will fail in terms of financial viability. Ireland’s first two onshore wind energy auctions struck a price of €75/MWh and €97/MWh respectively; more recently the price was €100/MWh, higher than the previous auction but not surprising due to supply chain costs and inflationary pressures. Our first offshore auction reached a strike price of €86/MWh. This is quite expensive compared to current wholesale gas prices which are currently €50/MWh. This means that Ireland’s offshore renewable energy prices are almost twice times the price of gas (October 2023) and the cost to the Irish taxpayer will be enormous. While the price of gas can be volatile due to market speculation and reaction to global events, the war in Ukraine and Germany’s long-term dependence on Russian gas and oil drove gas prices to €340/MWh in August 2022. Gas prices have now recovered due to abundant LNG supplies and reduced consumption.

This is a complex question for which there is no clear answer. What is known is that the increase in demand for energy from Data Centres puts a disproportionate and increasing burden on Ireland’s energy supply. While it is likely that some energy generated from offshore wind would be fed into the grid, current government policy includes plans to further increase the number of data centres the country will host, leading to a concomitant increase in energy demand.

Data centres are a high energy demanding industry, providing relatively little employment. A recent webinar hosted by Friends of the Earth, Ireland, provides very useful insight into the inadvisability of Ireland’s current Data Centre policy, and appeals for a re-think. A case in point is the current situation in Arklow.

The current promoters of the proposed Arklow Bank development, SSE, are aiming to construct 197m high turbines about 6 km from Brittas Bay and the Wicklow coast, in close proximity to Wicklow reef, (the first example of a subtidal sabellaria alveolata reef in Britain and Ireland), Wicklow Head SPA (a protected area for IUCN red listed Kittiwakes) and adjacent to the Buckroney-Brittas Dunes and Fen SAC, which hosts unique priority habitats, protected under the Habitats Directive.

Although this proposed project is very much in the early stages of planning, SSE appear to have already entered into an agreement to supply the energy generated to an Echelon Data Centre, and apparently further such agreements are envisaged. That this agreement has been reached in advance of the Arklow proposal even making an application for planning permission, raises serious questions about the planned use of Ireland’s offshore renewable energy. In addition, and perhaps of even greater concern, is that it creates serious doubt about the objectivity and impartiality of the planning and environmental assessment processes being put in place to manage wind farm applications. Though we recognise the urgent need for renewable energy, this should not be achieved at the expense of our marine environment in order to provide energy for data centres.

Because electricity is a commodity that cannot be stored efficiently, supply and demand must be matched at all times. Electricity generated from renewable sources such as wind and solar must be consumed immediately so it is fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas which are brought online to balance demand. As wind and solar do not consume any materials in the production of energy, they are the first sources used to supply the grid. As demand increases, fossil fuels are added according to how expensive it is to obtain electricity from that source. This hierarchy, where the addition of progressively more expensive fossil fuel powered generators are added to supply the demand, is known as the merit order.

Wholesale electricity prices are calculated on a half hourly basis and are dependent on demand; this is referred to as the spot market price. The spot price is determined by the last source of electricity to enter the grid (or to ‘come online’) which is normally a fossil fuel such as oil or gas. Therefore, no matter how much renewable electricity is generated, the wholesale market price is determined by the price of the last generator to come online. The initial spike in gas prices in August 2022 resulted in significant price increases, which are beginning to recover. Energy company hedging strategies kept prices artificially inflated in Ireland for almost 14 months after the spike. Given current market prices for natural gas, currently €50/MWh (October 2023) renewable energy is one of the most expensive generation sources to supply electricity in Ireland.

Badly. The last offshore wind auction (Round 4) in the UK resulted in a strike price of around €40/MWh, which is less than half of what Ireland recently achieved. The locations selected by the UK government for offshore wind were in areas approximately 45 km from shore and, in some cases, up to 135 km from shore. These projects would have incurred higher capital expenditure costs due to the distance from shore so the lower strike price achieved by the UK government is even more impressive. It is important to remember that the UK mainland is less than 100 km from Ireland and the same energy companies are involved. So why is Ireland’s offshore renewable energy so expensive?

The four Irish projects awarded contracts from Eirgrid are located approximately 10 km from shore, on shallow Annex 1 sandbanks and inshore fishing grounds. These locations should represent the cheapest option for developers, begging the question as to why the Irish offshore electricity strike price from ORESS1 is so expensive, at €86/MWh.

In the UK, the Crown Estate is responsible for the management of the seabed and facilitates competing demands for space by different sectors such as offshore wind, cables, pipelines. As managers of the seabed, the Crown Estate is the competent authority charged with ensuring that, in selecting sites for offshore wind development, legislation such as the Habitats and Birds Directives are adhered to so that high biodiversity value (e.g Natura 2000) sites are protected from impacts of the various activities undertaken at sea. How well this works in practice is unclear, but the system is designed to ensure that, in the face of the unprecedented expansion of offshore renewable energy infrastructure, sites are selected to minimise the associated increased risk to biodiversity.

The Crown Estate assesses areas for suitability and determines whether the Directives are satisfied before any seabed rights are awarded. The Habitats Regulation Assessment (HRA) must be conducted before any seabed rights can be awarded to developers. The support of relevant planning authorities and nature conservation bodies may contribute to the final decision.

In Ireland, the first offshore Maritime Area Consents (MACs) were awarded to seven proposed offshore renewable energy projects in December 2022 by the Minister for the Environment. The 45-year seabed consents were granted to ‘legacy’ projects located on sites self-selected by developers more than 20 years ago. These sites were never subject to Strategic Environmental Assessment (EU Directive) and are located on sensitive near-shore sites, close to fish spawning grounds and in high biodiversity value locations, and important bird areas previously proposed for designation as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) under the EU Habitats Directive.

The Maritime Area Regulatory Authority was established in July 2023 and will be the new authority for the awarding of consents, licencing, and regulation of Ireland’s inshore and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Current Irish offshore wind developments are proposed close to shore because they are located on sites that were selected by developers many years ago. From a cost perspective, turbines which are located in shallow water are less expensive to install and run. While this may be advantageous to the developers, such near-shore, poorly sited wind developments are likely to have devastating consequences for marine biodiversity, coastal processes and inshore fishers and will result in the industrialisation of coastlines and seascapes.

Although several early wind parks in the UK and Europe, including the current Arklow Bank turbines, were situated relatively close to shore due to technological constraints, most current offshore wind developments are sited more than 25 km from the shore, with some developments located as far offshore as 135 km. Because of a lack of proper ecosystem-based Marine Spatial Planning and Strategic Environmental Assessment, Ireland is the only country in the EU aiming to facilitate the siting of such large turbines so close to shore.

Table 1. Summary of distances at which low and medium magnitude of effect occur. National Resources Wales, 2019

Up to March 2023 the Irish Government encouraged a developer-led approach for offshore renewable energy projects, meaning that developers could pick and choose potential windfarm sites. However, a policy shift announced in March determined that windfarm projects would be developed via a new planning process. This new process involves windfarm developers competing for permission to build windfarms on sites preselected by the Government.

The selection of DMAP sites, within which developers then compete for permission to construct, should be determined by an ecosystem-based process. Unfortunately, in Ireland ecosystem considerations do not appear to have influenced the DMAP site selection process. Instead, high biodiversity value areas have been selected that encompass sites already targeted by developers, making a nonsense of the idea that Ireland is espousing a plan-led approach. Nonetheless, the decision to create DMAPs is Ireland’s first attempt at maritime spatial planning with regard to offshore wind energy development and, undoubtedly, is a welcome step because, in theory at least, it means that there is a commitment to a State-led planning approach to identify specific sites suitable for offshore renewable energy production.

Developed by the newly established Marine Area Regulatory Authority (MARA), Ireland’s first DMAP includes areas off Waterford, Wexford and Cork. Further DMAPs are planned for designation along our east coast, again an area where developers have already targeted vast areas of the coastal zone for development.

Yes. Several studies have indicated the possibility of negative impacts extending for distances of up to 60 km on marine life and marine habitat due to wake formation from turbines located in moving water. Additional sediment in the wake could cause a decrease in underwater light availability, negatively impacting primary production (e.g., phytoplankton survival and growth) and reducing the ability of sight-feeding predators to hunt their prey. It is also suggested that shifts in the patterns of suspended sediment will lead to changes in deposition or erosion patterns, risking reef smothering and increased erosion along Ireland’s coasts.

A 2018 study prepared for the Crown Estate (UK) identifies an increase of 40% in the concentration of suspended material in the wake behind monopile structures in an area where tidal flows were evident and further investigated several factors which would possibly cause increased sediment in the water. The study concluded that, along with scouring of the local seabed and the release of mud and organic material associated with epifauna (animals found to be living on or attached to the seafloor or submerged structures), the redistribution of suspended material from the lower water column to the surface is caused by the increased turbulence within the wake. (A study in the North Sea showed that hydrodynamic disturbance had a major impact on the whole ecosystem. Will try to locate.)

Did you know that the seven Arklow Bank turbines sit on monopiles. In 2017, Arklow Energy Limited, the company who managed the development, were granted a Dumping at Sea Licence for use of a sea plough to dredge 99,999 tonnes of material that had accumulated around the bases of turbines. The permit was granted for a period of eight years, with no environmental assessment.

The biodiversity disaster in Derrybrien, Co. Galway exemplifies what can go horribly wrong when wind developers and government neglect best practice, fail to ensure robust environmental assessment and disregard European environmental law.

In 2003, during the construction of the 70-turbine Derrybrien wind park, a landslide occurred causing over 450,000 cubic metres of peat to slide into the Owendalulleegh River, resulting in the death of 50,000 fish. The European Court of Justice subsequently ruled in 2008 that an Environmental Impact Assessment should have been conducted before the development was given permission to proceed. The ESB permanently ceased operations at Derrybrien in March 2022 and intends to fully decommission the site. In total, the State was fined over €20 million for failing to comply with EU legislation which resulted in this environmental disaster, with such serious consequences for the local community.

Community benefit funds are generated as a result of developers partaking in the government’s Offshore Renewable Energy Support Scheme (ORESS). ORESS is an auction-based system designed to guarantee developers a fixed price for their generated electricity over the lifetime of the project. In turn developers are obliged to donate (to the community?) €2 for every MW/hour they generate which may amount to approximately €2-4 million in contributions per year based on a development of the size that is proposed on the Irish coastline. This is a sizeable amount of money for communities but remember the guaranteed price paid to wind operators comes from the public purse and from us, the customers, and the ‘community benefit’ funds must be paid to communities regardless of how near or far from the coast a wind farm is located. Additionally, successful projects will be paid for electricity they generate even if the grid cannot accept the load. This may happen in times of high winds and low demand. In this case, the taxpayer will pay for electricity that is not being used.

Three recent government initiatives have led to the situation we are in today. The current position is that not one of the offshore wind developments currently proposed, including those being pushed by the government in their ‘Phase 1’ plan, have been subject to Strategic Environmental Assessment. In addition, more recent applications for investigative foreshore licences are being granted without being subject to Environmental Impact Assessment.

The three initiatives are as follows:

Firstly, in May 2020, while the country was in Covid lockdown, it was announced jointly by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage and the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment that seven offshore wind proposals would be classified as ‘relevant’ projects. This decision came out of the blue, was subject to no environmental assessment, no public participation and there was no access to a public right of appeal, possibly in breach of the Aarhus Convention.

Secondly, these same proposed wind developments, based on their special status as ‘relevant’ projects, were granted Maritime Area Consents (23rd December 2022) on the sole authority of the Minister for Energy, Climate and Communications, Eamon Ryan. A Maritime Area Consent (MAC) gave the developer 45-year occupation rights over a specified area of the Foreshore and the right to engage in the State’s Offshore Renewable Support Scheme (ORESS).

Thirdly, following the ORESS auction, four of the proposed projects were successful, meaning that they are now deemed eligible to apply for planning permission (development consent).

None of the projects first designated as ‘relevant’, then given MACs and subsequently allowed to proceed to apply for permission to construct were ever subject to Strategic Environmental Assessment. Difficult though it is to believe, this is the case and represents serious breaches of best practice and adherence to European law.

Yes. A Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) was undertaken pre-2010 when Ireland’s draft Offshore Renewable Energy Development Plan (OREDP 1) was published. However, while the plan was criticised for the acknowledged data and knowledge gaps, more critically, the Environmental Report of the SEA revealed that “a Parliamentary Statement, provided by Eamon Ryan, Minister of DCENR confirmed that the SEA should not influence or affect the processing of existing Foreshore Lease applications”. This Parliamentary Statement resulted in legacy applications being excluded from SEA and instead being categorised as ‘already existing renewable infrastructure’. Clearly the projects in question were not already existing infrastructure.

The OREDP was to have been fully reviewed and a new SEA carried out in 2020, but this has not happened. So, amazingly, none of the currently proposed ORE applications have been subject to mandatory SEA.

We want our elected representatives to be pro-active in safeguarding our marine and coastal ecosystems and ensuring they are not sacrificed for offshore wind infrastructure.

We want our elected representatives to make a public statement that you will support only Offshore Renewable Energy that fully complies with the following environmental safeguards:

- An ecosystem-based approach to planning and development –

the cornerstone of EU environmental law - The Habitats Directive

- The Birds Directive

- The Marine Spatial Planning Directive

- The Marine Strategy Framework Directive

- The Nature Restoration Law

We want our elected representatives to ensure that the State commissions a fully independent Strategic Environmental Assessment to ascertain the cumulative environmental impact of all projects proposed, and repeals Part 9 of the Planning and Development Bill 2023.

Click here to download a flyer of these requests